Grist Mills

Posted by Lois Ann Mast on

Grist mills became essential to the early pioneer families even though they were not yet built for most of our immigrants. Flour and cornmeal was a needed ingredient in every home to make bread, and the work of hauling wheat and corn to the mill and back was much preferred over laboriously grinding one’s own grain.

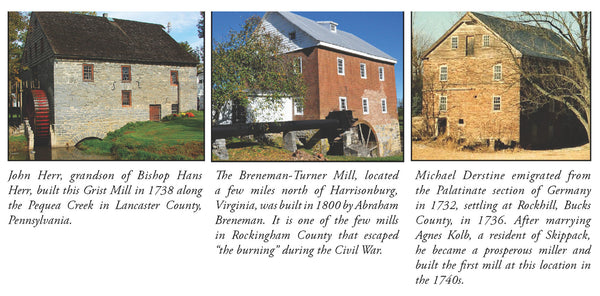

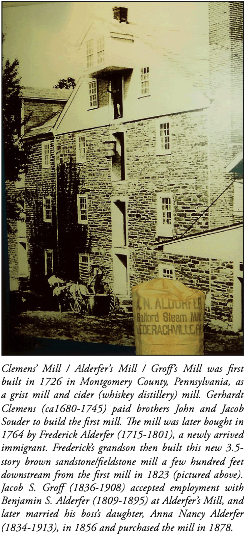

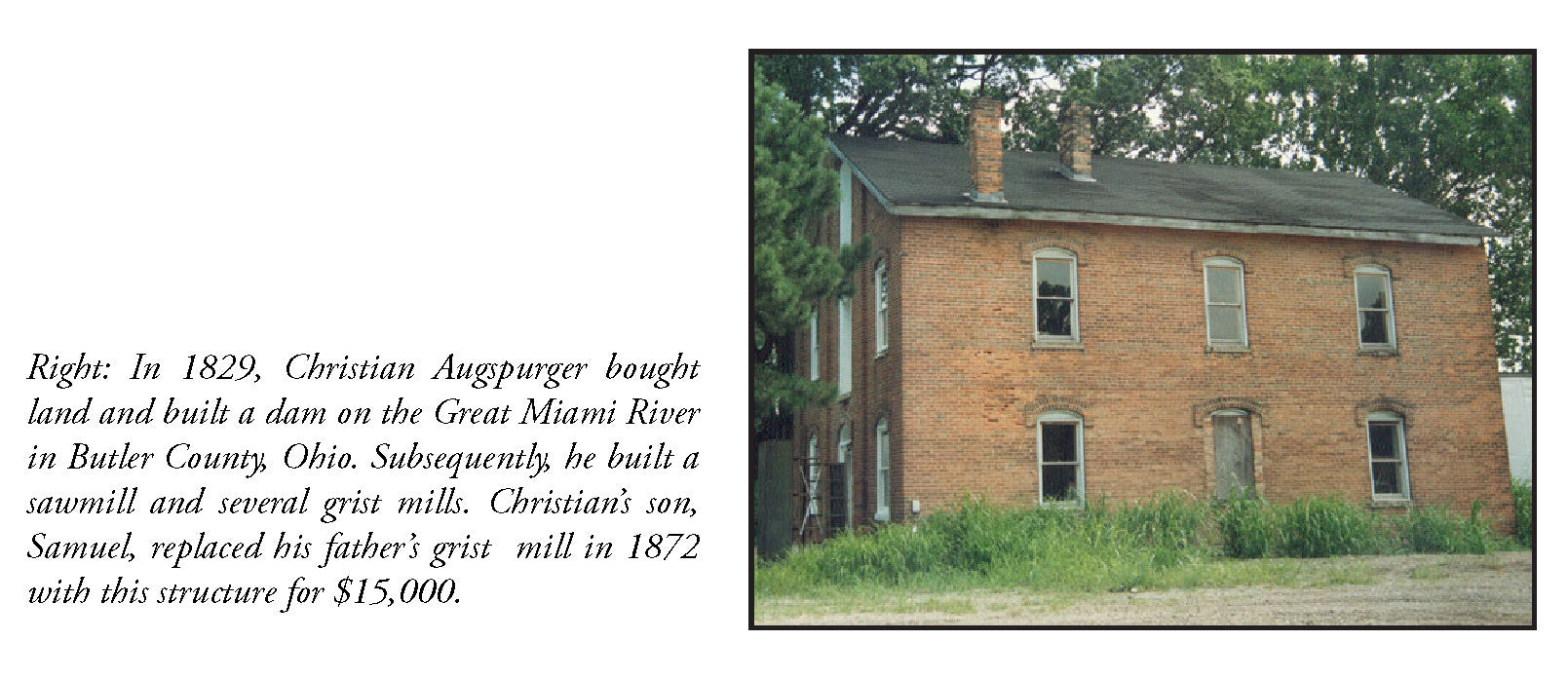

Pennsylvania was well known as the breadbasket of the thirteen colonies with more mills than in any other state. Many of the early mills were built by our Mennonite and Amish ancestors—some pictured on this page. Most are no longer working today, but even so, there are an average of 80 mill buildings standing in each of Lancaster, Berks, and Bucks Counties in Pennsylvania.

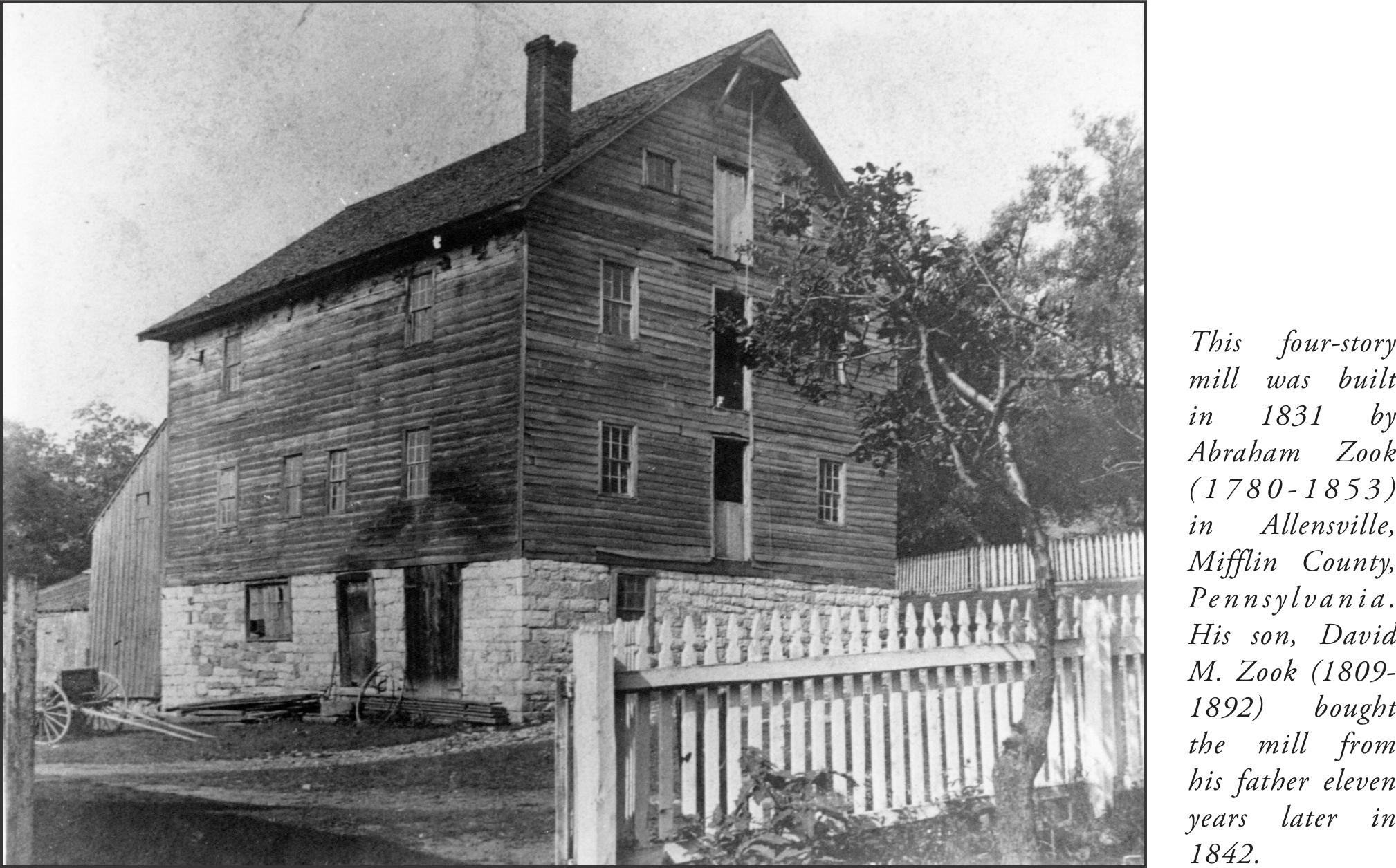

In the 1970s when I was researching my Zook ancestors in order to publish Only a Twig—A Branch of the Zugs/Zooks From Pennsylvania,1 I was fascinated that my gt-gt-gt-grandfather built an impressive mill in 1831 in Allensville, Mifflin County, Pennsylvania. Abraham Zook (1780-1853) was 51 years old when he built this mill with the help of his ten children—well, at least his five sons helped. One of his sons (my ancestor) was David M. Zook (1809-1892) who bought the mill from his father eleven years later in 1842.

This mill was operated by water power until 1880 when steam power was used. The dam that was used for water-power was made by Abraham Zook and his sons, with remnants still seen today even though the mill itself is no longer there. The lumber from the mill, as it was torn down, was used to build a factory that made concrete blocks in Allensville. Today, the Country Village Restaurant on East Main Street in Allensville occupies this building.

How the Grist Mill Works

In the colonial era, the average water wheel generated only a few horsepower, but that was adequate to grind grain. Although constructed largely of wood and stone, a grist mill was a true machine and a sophisticated one at that—it converted energy to work. Usually, a horizontal axle water wheel was turned by the falling water. A series of gears then changed the direction and speed of rotation to a vertical spindle connected to the grinding stone. Other powered operations in a mill often included raking the milled flour to cool it, and bolting or sifting the flour to separate it by particle size.

The churning of the big water wheel, turning grindstone, and the transformation of wheat into flour was hard work. Local farmers brought their own grain to be ground and would receive ground meal or flour back, minus a percentage called the “miller’s toll.”2

Early mills were almost always built and supported by farming communities, and the miller received the “miller’s toll” in lieu of wages. These communities were dependent on their local mill because bread was certainly a staple part of the diet.

Most of the early mills were water powered with a sluice gate opening to allow water to flow onto, or under, a water wheel to make it turn. Usually, the water wheel was mounted vertically, i.e., edge-on, in the water, but in some cases horizontally (the tub wheel and so-called Norse wheel).

The millstones themselves were laid one on top of the other. The bottom stone, called the bed, was fixed to the floor, while the top stone, the runner, was mounted on a separate spindle, driven by the main shaft. A wheel called the stone nut connected the runner’s spindle to the main shaft and could be moved out of the way to disconnect the stone and stop it turning, leaving the main shaft turning to drive other machinery.

In order to prevent the vibrations of the mill machinery from shaking the building apart, a grist mill often had at least two separate foundations.

Providing a Reliable Water Source

The power needed to operate the mill came from the large waterwheel. The waterwheel needed a sufficient supply of running water to make its revolutions. This was many times the difficult process of operating a mill.

To supply water to the wheel at a proper velocity, one needed to construct a mill dam and a canal known as a millrace to bring the water to the mill site. The trench that became the all-important millrace was sometimes several miles in length, and seven or eight feet deep.

The water then entered the mill through a wooden box known as a flume or penstock, and the miller could open a water gate from inside the mill to release water into the wheel to start to operate the machinery. The speed of the waterwheel varied depending on how much the miller needed to grind and how fast he wished to work.

Even after its construction, the millrace could remain a source of frequent trouble. Silt would deposit in the waterway and needed to be regularly removed. Storms also damaged the race, and repairs were frequently necessary. During the winter months, the water froze. And during the hot, dry summer months, the flow of water was not sufficient to operate the mill.

During times of plenty of rain, the mill could operate about nine months of the year; but in times of drought, the mill might only operate six months of the year.

As agriculture developed, the number of grist mills increased; for example, in Chester County, Pennsylvania, the number of grist mills grew from 72 in 1759 to 127 in 1781. By 1790, it was estimated that there were over 2,000 grist mills in the new nation. Fifty years later the number of grist mills and sawmills reached 55,000.3

Balmoral Grist Mill

While on a recent trip to Nova Scotia to visit friends, we toured an old restored mill at Tatamogouche in Nova Scotia. This three-story mill (pictured on the front cover of this MFH issue) is tucked away in a wooded gorge along Matheson’s Brook. One can still see grain ground, sifted, and turned into flour today just as they did in 1874 when Alexander McKay opened the mill.

It must have been a treat to hear the whir of wooden gears as the shifts and pulleys turned the granite millstones, as we imagine what life was like when our ancestors had no choice but to travel to the local mill to obtain flour or cornmeal.

We learned that it was unusual for a grist mill and a sawmill to occupy the same building, both obtaining their power from a single waterwheel. However, it was considered more profitable to separate the two activities to increase the efficiency of the mills and lessen the hazard of fire.

Once again, it was impressive how hard our ancestors worked in order to thrive and raise their families in a land where they were no longer persecuted as their ancestors were in Europe.

*MFH Editor Lois Ann Mast, has always been interested in the early grist mills that were so vital to our ancestors’ livelihood especially after learning that her great-great-great-grandfather, Abraham Zook (1780-1853), built a grist mill in Allensville, Mifflin County, Pennsylvania.

For more articles on Amish, Brethren and Mennonite History subscribe today.

Share this post

- Tags: MFH Article